The Future of Private Mini-Grids in Kenya

Kenya has made steady progress in expanding electricity access over the past decade. As a result, the national electrification rate has risen from 37 percent in 2013 to about 79 percent in 2023[1]. Despite this progress, many households in remote and sparsely populated areas still lack electricity. Extending the national grid to such areas remain prohibitively costly and technically challenging. To address this, the government has increasingly embraced off-grid solutions as part of its overall electrification strategy. Through the Kenya Off-Grid Solar Access Project (K-OSAP), the government introduced a plan to construct 120 mini-grids across 14 underserved counties. This project will significantly expand access to modern energy in underserved regions, further reinforcing the role of mini-grids in Kenya’s broader electrification efforts. However, even as these efforts continue, questions remain about the future of private mini-grids and what is needed to make them sustainable within the country’s evolving energy landscape.

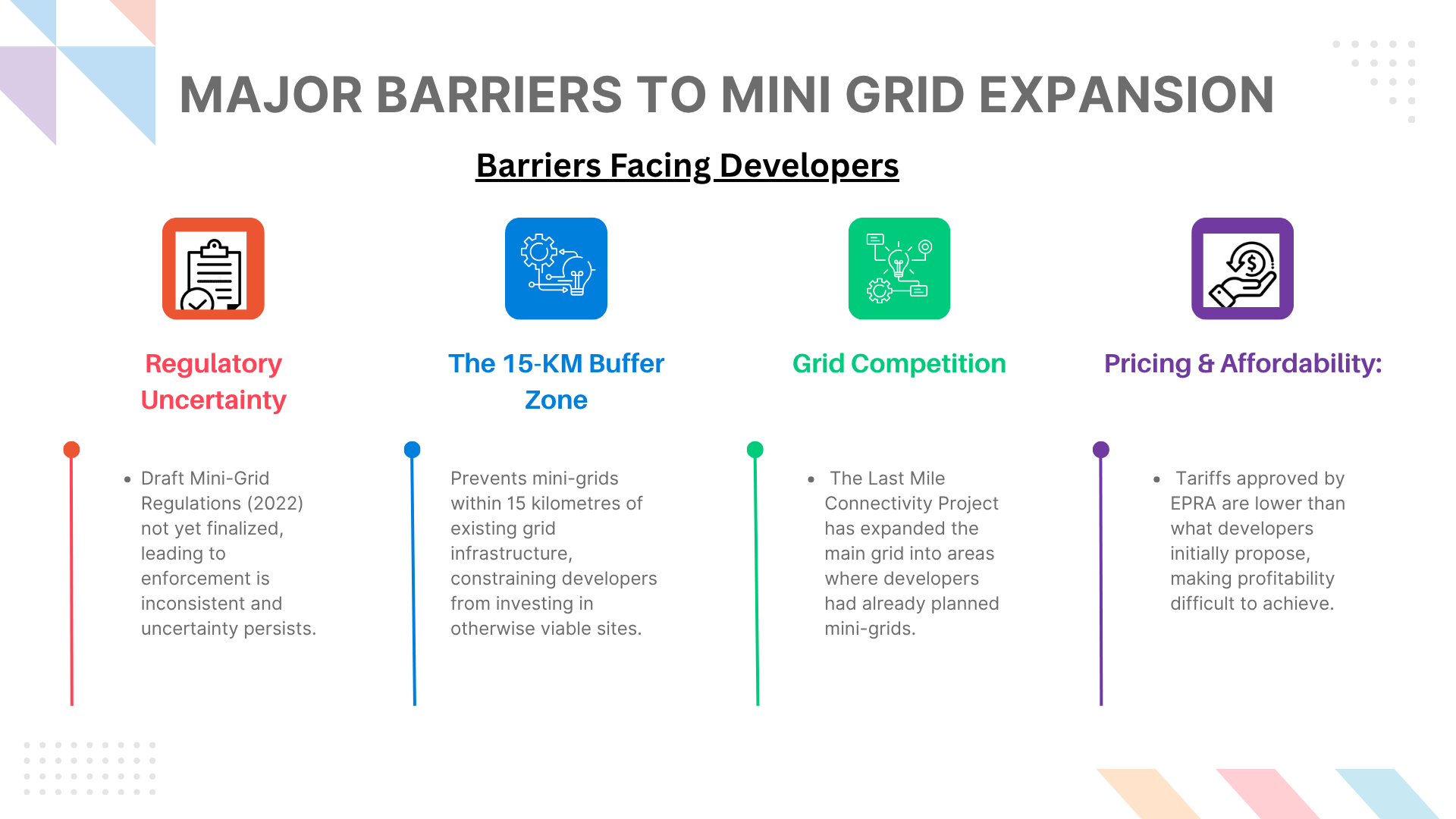

Before the Energy Act of 2019, the sector was largely unregulated and struggled due to weak policy and institutional coordination. The draft Energy (Mini-Grid) Regulations, 2022 was designed to establish clear rules for licensing, site exclusivity, tariffs and community engagements. However, since it remains in draft form, enforcement is inconsistent and uncertainty persists.

Among the provisions affecting mini-grid expansion is the 15-kilometer buffer zone established under the 2018 Kenya National Electrification Strategy (KNES). This rule prevents mini-grids from being developed within 15 kilometres of existing grid infrastructure. The intent was to avoid overlap with planned grid extensions, but in practice, the buffer has constrained private developers from investing in otherwise viable sites. Developers note that the restriction often eliminates areas with strong commercial potential, leaving only locations that are too remote or uneconomical to serve. Some private developers have also raised concerns about the Last Mile Connectivity Project, which has expanded the main grid into areas where they had already planned or begun setting up mini-grids. As a result, developers remain uncertain about how future regulations will affect their investment decisions.

Pricing and Affordability Challenges

Private mini-grids, particularly those powered by solar photovoltaics, often charge higher tariffs than the national utility, Kenya Power. Developers typically propose tariffs based on their cost structures and submit them to the Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority (EPRA) for approval. The regulator then reviews and adjusts these rates to protect consumers from excessive charges. While this process ensures affordability for end-users, it often limits developers’ ability to recover their full costs. In most cases, the tariffs approved by EPRA are lower than what developers initially propose, which makes profitability difficult to achieve especially since most customers have low and irregular incomes. High installation and maintenance costs, coupled with low electricity demand create additional financial pressure.

To address this, some developers have adopted tiered or time-of-use pricing, offering lower rates during off-peak hours to stimulate daytime consumption while others provide discounts for high-usage customers. However, constrained by cost, many consumers limit electricity use to lighting and phone charging, avoiding appliances with high power consumption. This limited use of electricity constrains revenue generation and slows progress toward broader productive use of electricity which is important for both community development and the long-term sustainability of mini-grids.

Community Expectations and Political Dynamics

Community expectations and local politics play a major role in the success of mini-grid projects. In Turkana County, residents complained that mini-grid tariffs were too high and expected to pay the same rates as grid-connected customers. Many also assumed they could use any type of appliance, only to discover that load restrictions applied. Such frustrations often arise when communities are not adequately sensitized before project implementation. In Busia County, one developer faced long licensing delays as officials from both the Ministry of Energy and EPRA reportedly requested informal payments, which increased project costs and delayed implementation. Political influence has also disrupted some projects.

In Kisii County, misinformation spread by local leaders led residents to believe that a mini-grid project would block Kenya Power from extending the grid to their area. The resulting hostility caused vandalism and theft of equipment, forcing the developer to abandon the site. These cases highlight the importance of early community engagement, transparency, and political neutrality. Developers must work closely with local leaders, communicate tariff structures clearly, and manage expectations well before construction begins.

Regulation, Grid-Readiness and Investor Confidence

The government requires all new mini-grids to comply with the Kenya National Distribution Code to build grid-ready mini-grids. This approach is intended to support long-term planning and prevent duplication of infrastructure. However, this policy has created uncertainty for investors. Developers are unsure what will happen when their systems are integrated into the grid. Without clear protocols for compensation, asset transfer or operational continuity post-integration, investors remain cautious.

The grid-ready policy is therefore both a solution and a challenge. It supports national planning but also raises concerns about the future of private participation in the sector.

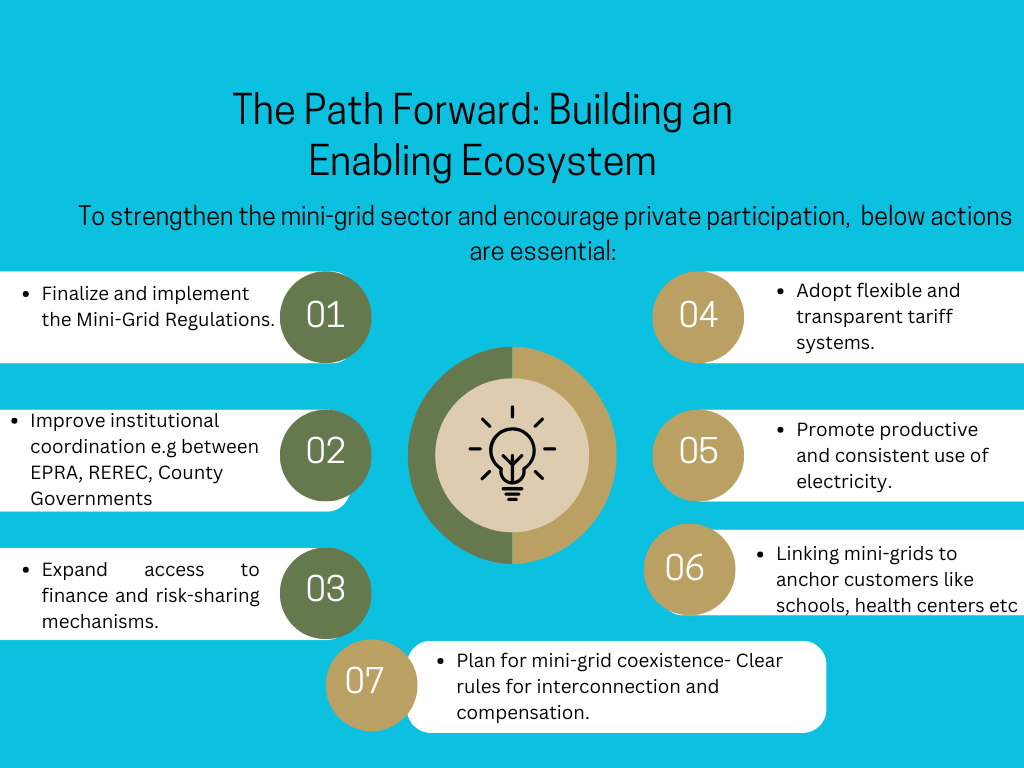

Building an Enabling Ecosystem

To strengthen the mini-grid sector and encourage private participation, several actions are essential:

- Finalize and implement the Mini-Grid Regulations: A clear and enforceable framework will create predictability, align national and county processes and build investor confidence.

- Improve institutional coordination: Clearly defining the roles of EPRA, REREC, county governments and the Ministry of Energy will streamline approvals and reduce overlap.

- Expand access to finance and risk-sharing mechanisms: Concessional loans, guarantees, and results-based financing can help developers manage upfront costs and extend service to lower-income communities.

- Adopt flexible and transparent tariff systems: Pricing structures supported by targeted subsidies ensure both developers recover costs and consumers access affordable electricity.

- Promote productive and consistent use of electricity: Many mini-grids operate below capacity because local demand is limited. Encouraging productive uses of power, such as agro-processing, small-scale manufacturing, and cold storage, can strengthen local economies and stabilize revenues.

- Linking mini-grids to anchor customers and appliance access: Integrate schools, health centers, and enterprises as anchor customers to create steady demand. Pair this with appliance financing and microcredit to help households and businesses afford high-utility devices from project inception, improving long-term sustainability.

- Plan for grid–mini-grid coexistence: Clear rules for interconnection and compensation will ensure that public and private investments complement each other rather than compete.