Resilience – A channel of hope or just a fashionable jargon? An African Community Lens: Grounded Perspectives

Interpreting resilience in a (more) complex century

A conceptual exploration.

Notwithstanding the context, you possibly in the recent past have been tagged/tagged others as ‘resilient’. Well, if not, you at least won’t fail to notice the buzzing interest in the concept on (international) social discourses and political agenda. The extant globally destabilizing Covid19 pandemic, and the heightened severity of climate stressors and other shocks continue to fuel to the popularity of the term ‘resilience’. There is an overwhelming body of literature on resilience, much of which attempt to unravel the conceptual complexity and contestation surrounding the concept. In fact, the larger share of academic works developed after Crawford Stanley Holling’s groundbreaking work on resilience in 1973 scrutinize (through pages and pages) the controversial definitions of resilience, eventually leaving you with the ‘there is no universal definition’; ‘existing definitions don’t work’; ‘need for review and homogenization’ duds. Without interpreting what meanings and attitudes vulnerable communities attach to resilience, then we (researchers) continue to scratch where it does not itch, with an even higher risk of contributing to “scholarly bullshit.”

I laud @Julian Kirchherr for his brave move to call out researchers for doing meaningless urban studies. Check out his article here for a little provocation.

Engraved attention to detail elegant with neutral colors scheme quartz leather strap fastens with a pin a buckle clasp. However, the same reason also makes it messy. If someone is having a bad day. Every food has a point value.

Without interpreting what meanings and attitudes vulnerable communities attach to resilience, then we continue to scratch where it does not itch, with an even higher risk of contributing to scholarly bullshit.

While this soul-searching in literature continues, 3 trends are manifest. First, the shift from the most skeletal understanding of resilience as “bouncing back” to a more rational framing that considers resilience as an evolutionary process of preparedness and persistence, adaptation, and transformation. Second, the reduced obsession with the end-state and more appreciation for processes; shifting from the notion of urban resilience as an outcome (the state of being) into that of resilience as a process (the state of becoming). Third is the increasing responsibilization of communities and the third sector actors into resilience building, which traditionally was exclusive to the state. This points to neoliberal disaster risk collectivism and decentralization of resilience governance to grassroots actors; a subject deemed relevant but with dearth evidence by the international community i.e., UNDRR, UN Habitat urban resilience hub, World Bank, and others alike.

Successful practices of resilience building increasingly reveal that resilience is place-centred, demanding a contextual understanding to the concept, and a human centric model of measurement. This becomes even critical in urban informal settlements which are distinctly heterogenous and demonstrate unique levels of vulnerability that have an impact on social, economic, and political capacities to deal with shocks

Contextualizing the resilience paradox.

Vulnerability among the urban poor.

The latency of resilience means that it is impossible to measure and observe in a risk-free context. Only communities (or systems) that have been exposed to risk can be termed as resilient (or not). The risk profile is highest among the urban poor in informal settlements (slums, favelas, shanties, barrios) of the Majority world, attributable to the increasing hybridity and multiplicity of disasters.

For these over 1 billion people, risk is continually exacerbated by the fragility of the living environments, extreme poverty, overcrowded living, infrastructural gaps, socio-political tension, and state ambivalence. In fact, in African cities, with approximately a third to half of urban populations being housed in slums, informality presents one of the most unabating urban challenges, glaring and manifesting as a regional disaster. This ‘hidden’ emergency has been brought to light during the Covid19 pandemic, forcing state and non-state actors to invest significantly in prevention and emergency response to the outbreaks and their interconnected risks.

In African cities today, a third to half of urban populations are housed in slums, presenting informality as one of the most unabating urban challenges, glaring and manifesting as a regional disaster

While such cross-sectoral efforts attempt to build community resilience i.e., improve capacities of vulnerable communities to accommodate and recover from the effects of a shock in a timely and efficient manner, it is impossible to back meaningful resilience practices without understanding what resilience really means to the most vulnerable.

Informal settlements may be largely bundled together as global hotspots of vulnerability, but I cannot stress enough their individual uniqueness and heterogeneity. They differ vastly in terms of culture, belief systems, social structure and political alignment, asymmetrical power relations, geospatial realities, organization and agency, social bonds, bridges and links (networks). This heterogeneity means that subtle contextual differences cannot be ignored as they influence how resilience is interpreted and practiced. The popular “one-size-does-not-fit-all” heuristic hints at this notion.

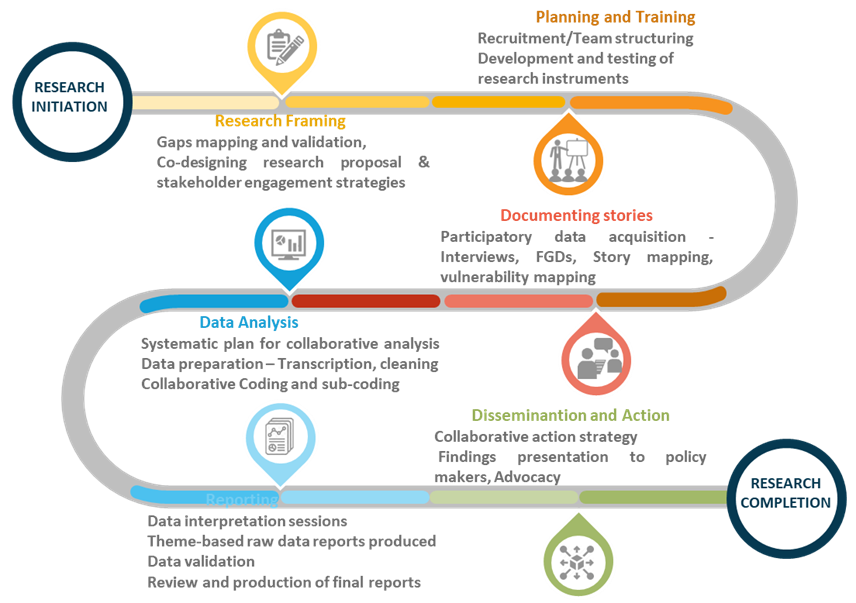

In our work, participatory action research proves to be a useful ‘tool’ to unpack resilience from a slum dweller’s lens. One of our studies has recently used an incremental, relational process of citizen science with community members as co-researchers, not merely participants as is the convention. The study, co-designed under the urban research and collaboration program explored resilience pathways in Mathare and Korogocho with community co-researchers from Ghetto Foundation. This partnership centralized lived experiences and treated local perspectives as research stories instead of research data. The approach reveals evolutionary narratives and practices through which slum dwellers interpret and construct resilience and reduce vulnerability.

Communities in Mathare and Korogocho largely perceive resilience as a desirable trait and in an equal measure, a pathway to long term sustainability. Our analysis establishes that the 2 settlements have undergone 3 distinct phases which influence how resilience is interpreted and practiced:

- The emergence round in the 1970s and 1980s when the settlements experienced rapid growth, social bonds thrived fueled by trust, and government forged productive collaborations with local community actors to deliver services.

- The conflicts round in the 1990s which marked the beginning of the ‘struggle for power’ – gangs took over service delivery and government withdrew from the settlements.

- The divergence round from the 2000s where self-organization (community agency) and government-initiated upgrading determined the growth trajectories

The snapshot of findings discussed here mainly refer to the 3rd round. We observe a distinct attribution of community resilience to social and human capital assets. In the former, the urban poor cope with shocks through social bonds (neighbors support, patronage, kinship), and connection to civil society i.e., NGOs. The latter asserts to individual risk responsibilization, with resilience being associated with (better) education, employment, skills, health, safety, and personality attributes.

For the ‘self-made’ 51-year-old Mutheu (not his real name) who supports his family from a technical skill learnt from his father, community resilience is not a choice to be made, it is an inevitable mode of survival. “Life in the ghetto is not easy, we live in insecure place, if not being stolen from then fire outbreaks becomes an issue…..so one has to be resilient to deal with such situation,” he says. In the same breadth, the narratives of other residents stress personal traits of hard work, perseverance, patience, persistence, hope, self-reliance, creativity/smartness, and religious association (praying to God), as precursors of community resilience.

For the voluntary community worker, Nekesa (pseudonym), resilience is a collective affair, community members finding it individually rational to cooperate with neighbors during crises. “We are resilient because we work together and are united, especially when there is something that has come out like cholera outbreak, we unite for it not to spread” she says. Social solidarity against crises was further grounded through examples of Covid19 response, where a resident terms themselves as “woke communities” – capable of self-organizing, activating youth groups, and taking initiative.

To add weight to risk collectivism, other residents bring to the fore the critical role of the third sector – “…here resilience is community coming together to work on something …I have never seen the government, NGOs and community working together; only NGOs are working closely with the community.”

The diverse actor arena and the community’s positive connotation to the concept of resilience means that its value at the grassroots remains undisputable but so is its capacity to raise contention.

Mixed feelings about resilience…?

For the voluntary community worker, Nekesa (pseudonym), resilience is a collective affair, community members finding it individually rational to cooperate with neighbors during crises. “We are resilient because we work together and are united, especially when there is something that has come out like cholera outbreak, we unite for it not to spread” she says. Social solidarity against crises was further grounded through examples of Covid19 response, where a resident terms themselves as “woke communities” – capable of self-organizing, activating youth groups, and taking initiative.

To add weight to risk collectivism, other residents bring to the fore the critical role of the third sector – “…here resilience is community coming together to work on something …I have never seen the government, NGOs and community working together; only NGOs are working closely with the community.”

The diverse actor arena and the community’s positive connotation to the concept of resilience means that its value at the grassroots remains undisputable but so is its capacity to raise contention.

Mixed feelings about resilience…?

During the narration of his story of resilience, Matheka (pseudonym), a community health volunteer) is hesitant to describe his community as resilient or not. “…because Mathare is for low class people … we are like soldiers. We must work hard to succeed, it is just survival for the fittest. To say if we are resilient, it depends on who is asking”, he says. In his view, a resilient community is just a nomenclature that upholds community agency but relieves the government of its responsibility. He explains that Mathare residents have faced multiple (sometimes interacting) shocks i.e. cholera outbreaks, gang violence, extrajudicial execution of youths, fires, ethnic conflicts, post-election violence, covid19 pandemic among others, but they have survived. While this demonstrates attributes of a resilient community, his view is that being tagged as a ‘resilient community’ would exclude them from future (non-)state plans. This resonates closely to the outcry of hurricane Katrina’s victims who demanded to NOT be called resilient again.

“every time you say, “Oh, they’re resilient, it actually means you can do something else, something new to my community. … We were not born to be resilient; we are conditioned to be resilient.” Kaika, 2017

In such a case, while it is expected that state and non-state actors will augment the adaptive capacities of the ‘survivors’, they are considered capable of surviving more, new shocks – can be seen as penalization. These trends negate the resilience dialect forcing communities to use it, only when the conditions are right! The action arena of (community) resilience also distinctly raises tension. Mistrust and lack of transparency are cited to compromise risk collectivism. A community leader in Mathare observes that Community Resilience Initiatives (CRIs) especially those targeting livelihoods fail or stagnate because “Nowadays people don’t cooperate when it comes to saving together due to insecurities and trust issues”. Compared to the 1970s and 80s (emergence round), there is significantly less collective saving and investment in emergency and long-term activities.

In the same light, mistrust spills over to cross-sectoral actors. A resident in Korogocho narrates that “There before [in the early 2000s], there was cooperation when working with the NGOs when going to the government offices to demand for security and other needed basic needs in the community but nowadays, things have changed and they (NGOs) do things their own way.” Several respondents also raised disapproval of ‘cosmetic’ community engagement by NGOs in resilience activities – an implicit tokenism further explained in the Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation. Nekesa, (cited here previously) also asserts to the government’s laxity in resilience matters.

On one hand, the narratives spotlight the role of social bonding in navigating crises (especially where the state role is blurred), but on the other hand portray them as equally vulnerable to shocks. Angaza (pseudonym), a 25-year-old construction worker says “When I see an opportunity to earn I get it and I also involve my friends, this has changed during the corona time everyone is checking on themselves and their families, for those who are not lucky enough to get opportunities find it hard.” This indicates that the relational position of social capital assets (including bonds, networks) within a vulnerable community means they are equally vulnerable – their capacity to preserve their role and create value during crises is also put to the test.

Focus group discussions further revealed the various ways in which community resilience is romanticized. Some coping mechanisms may be counterproductive for resilience e.g., engaging in Chang’aa brewing, youth groups eating their chicken (investment) during covid19; while others may be exploitative and increase the (future) vulnerability e.g., children dropping out of school to help in parents business.

These snapshots increasingly reveal that how other actors perceive resilience has an impact on the investment they put towards building and sustaining it. Building community resilience for over 2.4 million urban residents in Nairobi (over 60% of the capital’s population), requires amplifying the nuances emerging from this research.

So What Now?

The research underscores the role of grounded community perspectives in building a practical understanding of community resilience, co-creating meaningful resilience initiatives, and cautiously calls scholars and policy makers to the cognizance that resilience can also be romanticized!

So What Now?

Nairobi, and other 4 cities (Mombasa, Kisumu, Eldoret, Nakuru) through the World Bank’s funding are in the process of crafting their Urban Resilience Strategy, supported by Geodev Kenya Ltd, under the superintendence of State Department of Housing and Urban Development. The grounded perspectives of the urban poor in informal settlements are crucial to contextualize (community) resilience and (re)define the “stake” in multi-stakeholder collaborations for resilience building.

State actors are challenged to take up more proactive roles and amplify their contribution in resilience building. Literature underscores that they (especially local authorities) are the backbone of resilience, and an even louder call for them to work with local communities, grassroots organizations, local entrepreneurs, NGOs, and other third sector players to avoid missing subtleties and contextual factors.

Resilience does not replace sustainability; it is rather it is a state of becoming more adaptive, pathway to achieving long term sustainability. It is high time that practitioners marry sustainability and resilience agenda, both at community and city levels.

The study also points to areas of authentic scholarly contribution. Well, since I started with a provocation that researchers need to step out of the vicious cycle of producing ‘scholarly bullshit’ it is only right that I highlight some critical conceptual and practical gaps.

First, there emerges fuzziness in understanding who is responsible for resilience building at the community level; an individual/community/international community/civil society/state responsibility? Do they all have a stake? How should the “stake” be best operationalized in effectuating meaningful emergency response and transformative resilience.

Secondly, while there are ‘universally popular’ definitions of community resilience, the highly diverse resilience knowledge economy ought to centralize evolutionary narratives and lived experiences of local communities in contextualizing (community) resilience. This (also for practitioners) demands a paradigm shift first in our methods of producing science and publishing results. We hope our model of participatory action research, and co-publishing with community co-researchers is a step towards this shift.

Thirdly, the capacity of bonds and networks to preserve their role and create value for local during crises emerges as an interesting avenue for exploration.

Fourthly, my ink is running out, so I hope you are provoked enough to engage us (ICFI-Nuvoni) and our partner (Ghetto Foundation).

Related Perspectives

Physical Address

No. MK088, Ushindi West Avenue,

Mukuyu Rd (Mukuyu West Wing), Thome 1

Nairobi, Kenya

Organization

Subscribe for newsletter & get news, events and publications updates

Contact Us

Office Tel: (+254) 20 8009928 |

Mobile: (+254) 706 324 467

© 2025 Nuvoni Research