Unearthing the digital divide among the urban poor in Kenya’s Informal Settlements

Why this matters: Positioning the Urban Poor in the Global Digital Transition.

Technology is presently at the heart of human transformations and a measure of individual and societal development globally. In the modern world, digital access determines one’s social standing and on a national scale, shapes economic progression. A 10% increase in broadband penetration is seen to yield a 1.4% rise in GDP in developing nations (Khalil et al. 2009). Kenya has in the last two decades made noteworthy strides in technological advancement, evidenced by the development of the Konza Technopolis, licensing of more internet and cellular service providers, digitization of government services e.g. e-citizen platform, Ardhisasa, NEMIS (education), the institutionalization of ICT (through the ministry and corporations such as ICT Authority). There is an equally high rate of adoption evidenced by the growth of mobile subscriptions (133% of the population in 2022), increased installation of fiber optic per capita, and increased geo-coverage of fixed and mobile broadband.

Despite the digital progression, the urban poor communities in informal settlements remain excluded from the digital mobility which increases their vulnerability to multifaceted shocks. Our past studies at the advent of covid19 (2020-2021) have demonstrated communities can better adapt to shocks when they have access to digital services and information. However, households in informal settlements are heterogenous and the capacity of each to access and use digital solutions vary. This necessitated our study to understand the disparities in digital access and the implications on resilience.

Despite efforts to shrink the digital divide, among the urban poor, significant challenges deaccelerate these attempts.

Study Approach

In our diagnostics, we have adopted a Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach that uses Citizen science as a tool to ground this study on a synergistic conjunction of the experiential knowledge of residents, research skills of trained community researchers, and discourse knowledge of scientific researchers. We draw our sample from Mathare informal settlement, Nairobi, one of the most prominent ‘political settlements’ and the largest after Mukuru and Kibera.

Mathare residents are exposed to constant shocks of crime and police brutality, fires, evictions, disease outbreaks, poor housing, floods, water shortage, and electrocution among others; forcing them to devise adaptive mechanisms for resilience. The community and scientific researchers co-designed the research agenda on digitalization and at the onset mapped over 285 digital platforms used to cope with shocks through secondary and primary methods. Primary data was collected through 48 in-depth household interviews and 2 focus group discussions. Data is coded and analyzed collaboratively with community researchers in Atlas.ti.

Results

Understanding digital access among the Urban Poor

1. Access to Digital Infrastructure

Prominent digital infrastructure in Mathare was wi-fi and mobile broadband services. Moja Wi-fi, Mtaani Wi-fi, Poa Wi-fi, and private Wi-fi (within organizations or households) were cited. Access however varies across villages. Geographically, Moja Wi-fi has strong signals within Mabatini, Mtaani Wi-fi in Bondeni while Poa Wi-fi is sporadically located. Cybercafés complement the Wi-fi installations. These public digital infrastructures are privately operated and are available for pay-on-use. The settlement is served by mobile cellular broadband in Safaricom, Airtel, and Telkom. Electricity is informally supplied, with some settlements reporting intricate electricity governance systems. Hospital Ward, Gitathuru, Mathare 4B, and Kosovo lack electricity connectivity for over 1 year (since October 2021) due to cartelism-KPLC wrangles.

2. Access to Digital Devices

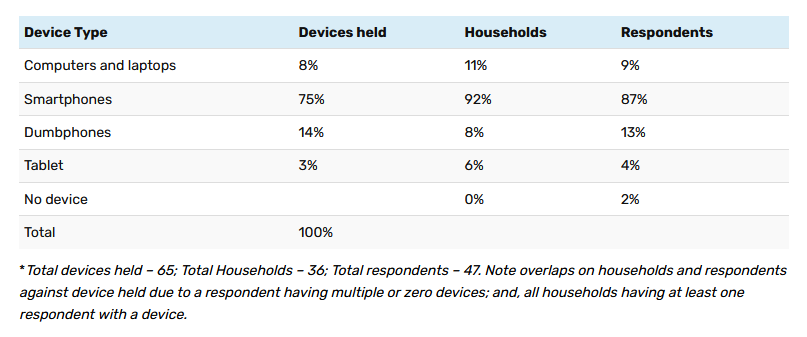

Digital devices aid in access and participation in a digital society and ultimately in bridging the digital divide. The study categorized mobile phones (dumbphones, smartphones, feature phones, and tablets), and computers (laptops and desktop computers) as digital devices. Computers and laptops are the least used devices by only 8% of study participants. Approximately 92% of households had at least a smartphone with some having more than one smartphone.

3. Internet Access

Approximately 79% of respondents have access to the internet. Broadband subscriptions, cybercafés, and wi-fi/hotspots (55%) were the main modes of internet access. Private internet access is mainly through the mobile broadband (87%) provided by Safaricom, Airtel, and Telkom, with a few cases of private wi-fi (6%) i.e., Faiba Mi-fi (I do not have wi-fi I have Mi-fi (MT13)), hot spotting by relatives and friends (6%), (…not unless for example, I have a hotspot from my sister’s phone when she purchases bundles (T34), or wi-fi from organizations within the settlement or at work (11%) (where I am [work] I have access to Wi-Fi… (MT13)). Public Wi-fi is less popular and manifests in the form of cybercafé (19%) and public wi-fi (15%) in Moja Wi-fi, Mtaani Wi-fi, and Poa Wi-fi. Cybercafés have been popularized by new education curriculum. Dwindling use of public wi-fi is due to its unavailability, inaccessibility, weak signals, and unreliability.

4. Digital Skills and Abilities

A less share of the respondents (13%) had attended basic computer training programs and possessed sufficient skills for their digital assignments. There is a close relationship between digital skills (the technical ability to download, access, and use platforms) and the age and education of respondents. The well-educated and young possessed better digital skills and abilities as compared to the aged. The youth transfer their skills to parents who in their absentia barely use smartphones beyond normal voice and text communication. An estimated 90% of smartphones and tablet holders possessed basic digital skills. However, technical limitations were highlighted in accessing and effectively using ‘complex’ platforms such as conferencing (Zoom, Google Meet), social networks (Instagram, Twitter, YouTube), health applications (Call-A-Doctor), etc. Further, 67% of dumbphone holders lacked basic digital skills. Majority of the sample, 87%, lack technical skills and abilities to maximize tech-based opportunities. Content creation and monetizing of social media platforms rank highest among digital skills inadequacies.

5. Affordability

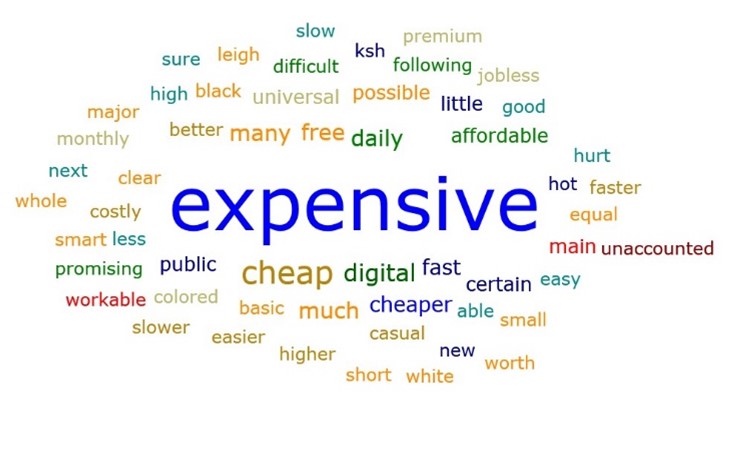

Costs related to digital access included the cost of acquiring digital devices and the cost of internet connectivity.

Device costs: Devices were acquired on either cash, as gifts, or on credit (mostly from M-kopa). New smartphone devices ranged between Kshs. 6000 and Kshs. 11000, secondhand options were acquired at Kshs. 2000, used dumbphones cost Kshs. 500 while new ones ranged between Kshs. 1000 and Kshs. 1300. This potentially explains why the majority of the devices acquired in cash were secondhand smartphones with only 17% of respondents having bought new smartphones. Computers and laptops were acquired as secondhand devices. There is a high market for secondhand phones, which potentially explains the increased phone snatching in the profile of petty crimes.

Internet connectivity costs: The average daily expenditure on internet ranged between Kshs. 5 to Kshs. 100 for mobile broadband subscription. There was an overreliance on Safaricom data bundles due to its speed and reliability despite been considered the most expensive. The average megabytes price ranged between 0.13 cents to 1 cent for Safaricom, 0.4 cents for Airtel, 0.3 cents for Telkom and 0.4cents for Faiba Mi-fi. Wi-fi connectivity and individual hotspot costs varied between Kshs. 500 to Kshs. 1000 per month. Moja Wi-fi was indirectly charged requiring residents to watch ads in exchange for bundles. Mtaani and Poa Wi-fi were pre-paid for directly through credit vouchers. An overarching limitation of internet access was the time capping for broadband subscriptions.

Characterizing the Digital Divide

Despite efforts to shrink the digital divide, among the urban poor, significant challenges deaccelerate these attempts. Significant manifestations of digital divide include: –

1. Exclusionary digital device and service prices

The prices of new devices are out of reach for residents who are forced to shift to second hand digital devices, use dumbphones or use neighbor’s/relative’s devices. This has contributed to a loss of opportunities. Many residents are left out of the digital world due to digital devices that cannot connect to the internet and devices malfunctioning (hanging, overheating, frequent shutdown), etc. “…I have never owned a smartphone” (MB4) “…for me, we don’t have TVs and my phone can’t even access it…” (MT7). “It [phone] annoys me because it hangs when I apply for jobs or when doing online jobs…” (MU14) “…and I was not registered because I did not have a smartphone.” (MK3) “…not all people have smartphones.” (MB18)

The high cost of internet bundles limits internet connectivity and ensures sustained hours of an internet blackout. The fact that over 90% of internet-enabled device holders subscribe to mobile broadband of between Kshs. 5 and Kshs. 20 means they are online for a maximum of two hours on the day they can afford megabytes. Mostly, broadband subscriptions are meant to activate free WhatsApp.

2. Limited options for internet connectivity and Digital Infrastructure

The available wi-fi installations are weak and unreliable (and one must watch unwanted ads for connection). Broadband costs are out of reach, limited to only those that can afford daily subscriptions. Electricity is informal, devices cannot be comfortably powered. Eventually, many are left out unconnected, denied of access to basic ICT participation. This to some extent explains loss of opportunities, installation of private mi-fi for those with economic ability (only 8% of households), private wi-fi password cracking etc.

3. Digital Literacy

Among the urban poor, there exists enormous skills gap that limits access to digital platforms, products and services, and overall consumption of technology. “…but for this Call-A-Doctor App, I don’t know how it functions…I need more skills…” (MB1) “I would like training…”(MK3). Notably, 93% of study participants recommended technical training and brought forth nuanced perspectives of feeling left out of a digitizing society. Despite having talents, they could neither showcase them nor monetize them. Digital skill inadequacies were prominent among the aged as were the uneducated, which increased their vulnerability to extortion, being defrauded and excluded. Digital illiteracy and lack of digital devices have also birthed a loss of dignity and privacy as some were forced to borrow devices or get support from neighbors and relatives.

4. Detrimental User Attitudes

The inability to access platforms and the internet among the urban poor was also attributable to personal choices, cultural beliefs, stereotypes, and ignorance. It is characterized by a lack of knowledge on the benefits of digital access and how to use technology as a tool to better one’s life, ignorance and illiteracy, unwillingness to participate, and failure to understand the relevance of platform access.

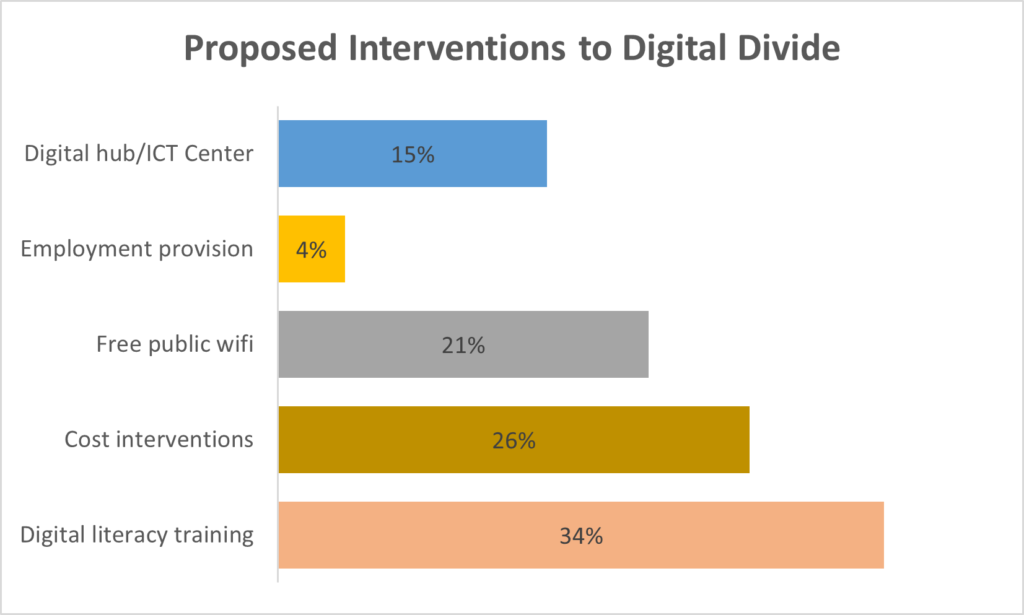

Towards positioning the urban poor in an inclusive digital transition

This research reveals the need to increase digital connectivity BUT underscores that presence of digital infrastructure does not equal digital inclusion. The fabric of the consumption of technology to bridge the digital divide lies more in addressing the underlying drivers of the digital divide. Economic and usability factors drive the digital divide narrowing down to the cost and affordability of digital devices and the internet, and the digital skills and abilities to use devices. As per the respondents, the attention to digitally transition the urban poor and bridge the digital gap should be three-fold:

- Installation of functional digital infrastructure and the attendant costs including device and internet cost reviews to meet the financial abilities of the urban poor, free public Wi-fi installation and installation of ICT centers/hubs

- Proactively establish digital literacy training programs that harness digital access and use

- Provide income opportunities that can sustainably guarantee consumption of technology.

Notes

This research was funded by the Erasmus Initiative Vital Cities and Citizens (VCC) and the Research Innovation Fund (RIF) of the Institute of Social Studies, Erasmus University Rotterdam. It is implemented by the International Center for Frugal Innovation (ICFI) (hosted in Kenya by Nuvoni Centre for Innovation Research (NCIR)) in collaboration with Ghetto Foundation.

We wish to thank Ghetto Foundation, Jan Fransen of IHS/VCC, Erwin van Tuijl of ICFI, and Elsie Onsongo of ICFI/NCIR for their contribution in designing this research, gathering and interpreting evidence.

Related Perspectives

Physical Address

No. MK088, Ushindi West Avenue,

Mukuyu Rd (Mukuyu West Wing), Thome 1

Nairobi, Kenya

Organization

Subscribe for newsletter & get news, events and publications updates

Contact Us

Office Tel: (+254) 20 8009928 |

Mobile: (+254) 706 324 467

© 2026 Nuvoni Research